Opening: 19th of September, 10 pm

This is not a room sheet. I simply wanted to share some

ideas about João's work and I think that this may be the right format, but it

probably isn’t. I'm not sure whether João fully identifies with my ideas about

his work. But he's an artist and that's how it works - it's part of the game.

When I play this game with his work I never know the extent to which I’m

actually manipulating the rules. It's like finding a deck of cards in the

middle of the street and being asked to play, or bumping into someone in the

street who you know from TV. This isn’t a question of mistakes, but

displacement – seeing something familiar in a different context, or something that

you think you know but the codes have changed.

João has a voracious visual appetite - he’s hungry as

a wolf. I would even say that he has a vocation for appropriation, but I think

(indeed I’m sure) that we’re not talking about appropriation in the conventional

artistic sense. We’re not talking about Dadaism, or Pop Art (perhaps just a

little bit). I think it’s something different, not the opposite, but that

exists side by side. It has much more to do with life and reality than with any

conceptual exercise. Rather than using the term “appropriation”, we could talk

about re-signification, personal re-signification, even emotional re-signification,

of things around us. I’m not talking about filling a void with a new meaning,

nor about a process of negotiation between things and their agreed meaning. I’m

talking about comings and goings, something between revolutionary theft and a

poster printed in a magazine that people then put in their bedrooms. Street fighter.

Things that are appropriated (or re-signified) are far

from being empty. They are often aggressively or surreptitiously ideological – as

things that were made to have a specific, non-negotiable meaning. That’s what I

was trying to explain: a re-signification, above all emotional, of these signifiers,

is a way of dealing with these monsters. Only this kind of sensitivity can

erode this unilateral dimension of the corporate production of symbols. I think

this refusal of universality is important. João needs to steal these things

because they are part of his life and now belong to him. They are his amulets.

They mean whatever he wants them to mean, or, removing this conscious dimension,

they start to signify something else, simply because they belong to him and form

part of his life. What do YOU represent

?? !!

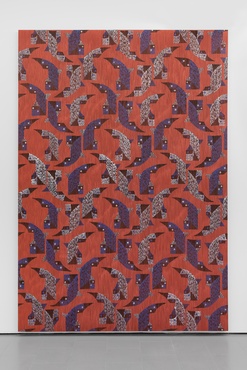

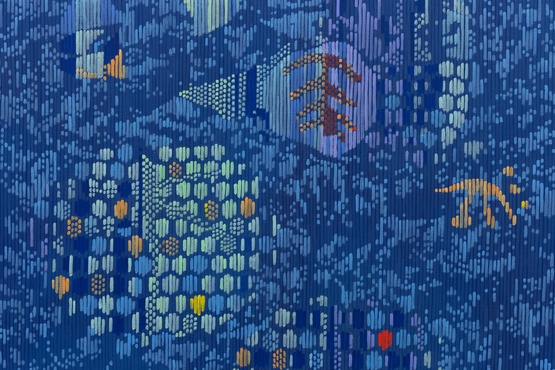

Patterns drawn anonymously in a textile factory department

to be used on bed sheets or bus seats become a backdrop for micro-events, journeys

or sleepless nights, rather like the geometric monotony of monochrome tiles or the

shiny covers of recordable VHS tapes. The mix of colours conceived to identify

a specific cassette brand now identify the experience of the film that has been

recorded, rather than the brand’s corporate image. Colours and shapes simply become

conductors, like electric wires, where the current flows in two directions, or

even non-communicating vessels, as if they had been insulated by thick layers

of rubber. References to art enter the work, sometimes in an absolutely honest

manner, due to genuine admiration, sometimes in an absolutely absurd manner,

due to the number of times they have been filtered and distilled by reality, as

if they could be used to produce an inverted visual historiography between the

pattern of the bus seat covers and the first modernist paintings. Either way,

depending on where you look, the distance between a Frank Stella painting and a

sticker may be minimal.

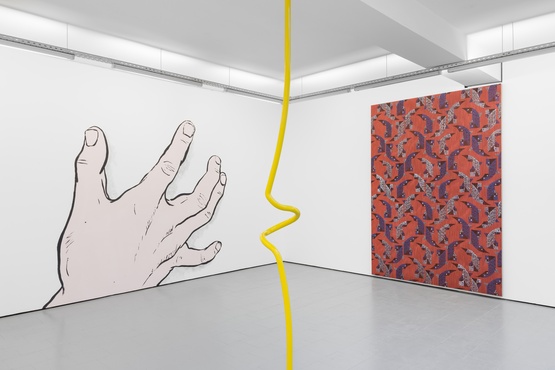

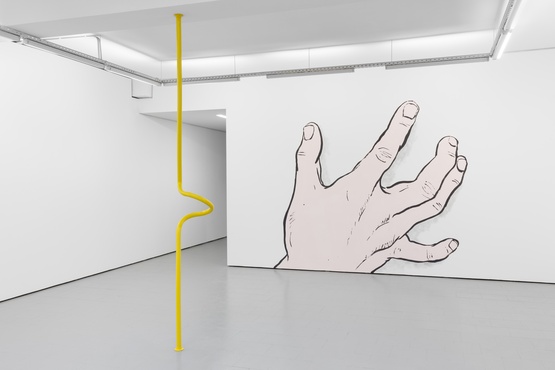

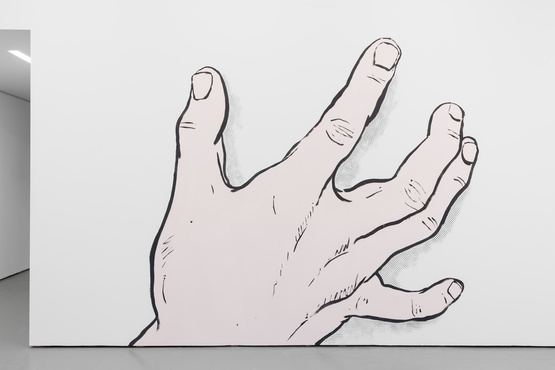

One of the works in this exhibition has tremendous

metaphorical capacity and offers an exemplary insight into João's work. A metal

pole that has been painted yellow vertically occupies the gallery space, from floor

to ceiling. The line should be straight but it has been twisted. The form

clearly resembles a pole that people hold in the metro to avoid falling over. This

entire sculpture is made to look like a pole. And the twist (just like the

bifurcations that begin to appear in the poles) were probably designed by a

team that was attempting to solve a problem. A two-metre pole can normally only

be used by two or three people. But this twist, this structural deformation,

increases the contact zone between the object and the people, which I think is

important. Deviations, twists, repetitions, patterns, and João's working

methods in general, like the design of the pole, serve to increase the contact

area between abstract forms and people, who continue their journey and probably

normally ignore the pole as they are looking at their mobile phones.

André Romão

September 2019