My little animal,

Arachne was known to be a talented weaver.

She challenged Athena to a competition.

Arachne is mortal.

Athens is a goddess.

Athena, disguised as an old woman, warns Arachne against defying the gods.

Arachne maintains her challenge.

*

They compete.

Their fabrics are compared.

Athena’s composition is classic.

Arachne's is baroque.

Athena uses the theme of her victories and gives praise to the gods.

Arachne denounces the abuses of the seducing and deceiving gods.

Athena’s fabric is beautiful.

Arachne's fabric is vivid and even more beautiful.

*

The competition is aesthetic and ethic.

Arachne wins on aesthetic grounds.

Athena wins on ethical grounds. Hencee, by force.

Athena represents the defence of established power, which Arachne challenges.

Arachne represents resistance.

Athena puts a curse on Arachne.

Arachne is metamorphosed into a small hairy animal and is ordered to make, unmake and remake her fabric with the thread issued from her belly.

Athena makes Arachne an example to others: do not dare challenge the gods in their work and do not denounce their actions.

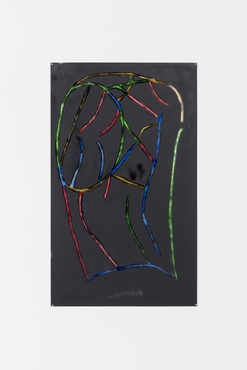

Arachne weaves with black thread, when she used to weave with bright colours.

*

Athena rips up Arachne’s fabric.

Athena will always rip Arachne's fabric to pieces, for all eternity.

Arachne will never again be able to produce a complete fabric.

However, Arachne will start over again. Without any regrets.

*

Textile and text.

Oral text, speech, use of the voice.

First: Arachne speaks.

Second: Athena silences and censors her.

Athena devalues Arachne's abilities and forces her into silence and invisibility.

Arachne isn’t incapable, she is simply incapacitated.

*

Girls have the greatest internalised fear of spiders.

But when they look beneath the suspended web, woven by a little furry animal, they see all colours, united in the black web.

- Black is, ultimately, the resistance of a continuous fabric of colours that our eyes normally don’t see and our ears don’t hear.

Rainbow

The exhibition of a set of works in a certain time and

place reflects certain choices and principles of representation. Representation

of the ideas expressed in a literary text, in visual and plastic terms (a word that we hope hasn’t gone into disuse, used to

refer to that which isn’t merely received through vision), is immediately

associated to a translation and, in a way, with an illustration. In this case,

solely by convention, a text[1] would occur first and be the original cause of the

(visual/plastic) works on display. But this concerns neither the translation

nor the illustration of a text - although questions inherently linked to

translation inevitably persist, when moving from one art to the other (i.e.

from literature to the fine arts).

In aesthetics, the issues inherent to representation

and translation have become a permanently open problem: either in terms of how

each art would specifically represent certain ideas, or should best do so.

Diderot - the founder of art criticism who made an undeniable contribution to

the development of aesthetics as a discipline - believed that each art has its

own hieroglyph: its own specific form of representation. He considered that it

is possible that certain ideas are better represented by one art than by

another, and for this very reason we inevitably compare aesthetic results (and

their effects). Hence, it both dangerous and erroneous to identify an original,

unique, prior and initial textual cause, on the basis of which this body of

work is presented. The danger stems from comparison and, consequently, from the

possibility of subjecting one art to another, i.e. of works carried out with

the text. This danger has little to do, as one might first suspect, with the

path of inherent distancing from the arts and their emancipation (and the

circumscription of their irreducible aspects). It is only related to a certain

intended distance at the time of reception. The error, which we propose to

correct, is to consider that the text is the sole cause. It is indeed a remarkable

cause, but is never unique. We would never have chosen it unless it revealed

something important to us, unless it touched us so profoundly in relation to a

current issue, with political ramifications and numerous and scattered

associations. The text in question is Diderot’s in-famous work, Les Bijoux Indiscrets. Who read it? At

the time, subversive philosophical ideas were often introduced into a text

considered to be obscene. As a result, the book was a great commercial success

and had many readers. Back then the reader, as in the present day, who expected

to find something truly obscene, would have found the text to be essentially

irritating. There are numerous, dense, and at times meaningless, digressions on

other subjects, far removed from the expected erotic content. There are

chapters devoted to aesthetic criticism (literary and theatrical), politics,

religion and the sciences. The compilation of so many subjects had a clear

pedagogical goal (as stated in the dedication to the young reader, Zima, in a

genuine act of initiation): the knowledge to be received, through exegesis of

the text, should occur with sensibility (and the senses) and understanding, in

a complete union between body and spirit, in line with a programme specifically

opposed to a certain metaphysics. The pretext for the narrative development of Les Bijoux Indiscrets is a fantastic

phenomenon, wonderful in character: in a distant time and place, a bored

sultan, eager for new amusements, asks a genie to help him. The latter gives

him a ring that gives the women of the court the power of speech (use of the

voice) through their sexual organs, while their mouths remain closed. In a game

of swapping the speech organs (by physiological analogy), a new discourse

emerges, considered to be true because it is located in the most intimate part

of human nature. First, the women reveal that they are dissatisfied, because

their indiscretions are now public knowledge. With the aid of machines,

resulting from technological advances, they try to silence the voice of their

sexes (their "jewels"). The muzzles are counter-machines - that

oppose the ring-machine - in a correspondence between causing to talk / and

causing to be silent. In this alternating confrontation between the language of

the mouth and the language of the sexual organ, and their respective voices, it

is possible to interpret the following: that all language is a cultural

construction and that the division of the sexes merely describes the degrees of

mastery of this construction. At one point, it is stated, with the inherent

satirical humour of Les Bijoux Indiscrets,

that men have not yet been given the gift of speaking through their sexual

organs, referring to the implicit fact that use of language is constructed in

them, and by them. For this reason, there would not be divergence between that

which is uttered by the sexual organs and by the speech organs. On the other

hand, the social, political and legal categories of women, as the “other”,

represented as being secondary to the masculine, is a projection that is

necessary for the knowledge and control by the masculine, as a builder of

language, of discourses. At the time of Les

Bijoux Indiscrets, which was a period of voyages of discovery (by sea and

land), the need to stabilise concepts (through the action of closing,

demarcating a circle) was assumed to be a source of security. The conception of

woman is a paradigm example of this. That which use of the ring permits, while

leading to confessions, is to scratch the surface of language and open it up to

truth, beyond its inevitable construction, thereby

making it possible to broaden the knowledge of that which is meant by a

specific category. Hence, if the definition of the category of woman (since

Antiquity) has been rooted in her sex, knowledge of her sex is opened up and

expanded through the display of multiple variants of erotic postures, embodied

in the “experiences of the ring”. And all other knowledge is thereby opened up

and expanded, with even greater relevance for a general philosophical

programme. In short, Les Bijoux

Indiscrets is a pretext for thinking about the body/bodies that is/are

defined, circumvented and delimited by the use of language and its discourses,

displayed as a platform for reflection.

In this exhibition, the ideas represented from Les Bijoux Indiscrets summarise those

that converge towards the goal of deconstructing categories through the

multiplicity of (existing) reality, using resources that are capable of

proliferating languages. Through the arrangement of the works, the construction

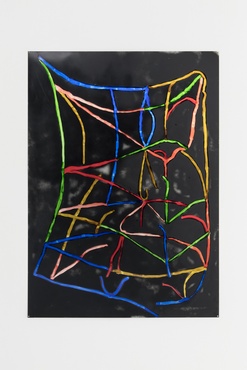

of a visual discourse adopts the metaphor of the rainbow. The rainbow is a

metaphor for language, open to multiplicities, to fusing and confusing

categories. The title of this exhibition is a play on words between arc-en-ciel (rainbow) and arachné (spider) - arc(a)c(hné)-en-ciel: a spider sky, a sky woven like a web of

associations. The spider appears in one of the illustrations of Les Bijoux Indiscrets (in the original

edition) and represents sensibility, branching of the nerves. The web is

therefore the construction that refers to the other (someone): from one

sensitivity to another. But it is also the common denominator, the essence of

all that exists and which abolishes that which manifestly stands before us

(e.g. the distinction between artist-producer and audience). It will be

possible to recognise forms such as the trachea and glottis (determining

physiological elements in the voice / speech), muzzles (corrupted, enabling all

voices to be heard, whether or not they are constructed, or are effectively or

poorly articulated) and the colours of the rainbow associated with the names of

the speakers (CIDALISA - CÍPRIA – CLEANTIS – EGLÉ – ERIFILA – ESFERÓIDE – FANNI

– FARASMANE – FATMÉ - FENIÇA – FLORA - FRICAMONA - FULVIA-GIRGIRO - HARIA -

IPHIS – IPSIFILA – ISEC - ISMENA - LEÓCRIS - MANILA -MIRZOZA – MONIMA – OLÍMPIA

- ORFISA – SALICA - SERICA – SIBERINA - SOFIA - TÉLIS - VÈTULA – ZAIDA – ZEGRIS

- ZELAIS - ZÉLIDA – ZELMAIDA – ZIMA […]). The illusion (in the iris) of a

colourful arc that is projected into the sky, is enhanced by another

construction (woven, as in the myth), which furthers the proliferation of

senses, to unleash the violence produced by the imposed categories.

Look at your life as if it were a web.

First, it's a place that you don't choose. The angle between two branches. The distance between a pillar and a doorway that you’re left with. The span of a ruin.

Next, it requires a calculation. The leap assisted by the wind that passes through the branches of the tree. The drop you projected between the gravitational force and the resistance to this force. The void you will fill with the construction.

There is also the thread that issues from you, the material that fills the leap, the fall or, in any case, the void.

Your life will be like the web: a reality without order, a desire without reality, and a life whose only raison d'être is your own existence.

The web harbours an undeniable unity between the spider's body and the bodies born from it, or that die because of the web, whether by chance, intent or need. As in life. But equally the web harbours an undeniable chaotic instability, which leads the spider to remake it in many other forms, avoiding that which, for various reasons, was destroyed in the tree, door or in the ruin of either.

Imagine that you are a spider: you make and unmake, but always in a way that we would say is paradoxical, because the spider is simultaneously automated and inventive. In fact, the spider has "genius", in the meaning given to this term by Diderot. Its mode is not mechanical, but it has a machine-like quality: it does what it has to do, enabling 1001 variants of the same plastic structure. The "genius" of each being is not related to whether it is sensitive or insensitive, rational or emotional: genius is simultaneously this and that which is not quite this. Unlike the machine, which operates "mechanically", without considering the where, when, how and why, genius, like the spider (when we say "spider" we might just as well say "author" or "actor"), operates automatically, observing certain laws that imply an element of ingenuity, disciplined energy. In his definition of the project of the Encyclopaedia, Diderot placed the editor between the stable infinite (“When we treat of beings in nature, what better can we do than to list scrupulously all their known properties at the moment when we write?”) and the unstable finite (“observation and experimental physics, constantly multiplying phenomena and facts, and rational philosophy, comparing and combining them, extend or contract constantly the boundaries of our knowledge, and consequently introduce variations in the meanings of our established words, render the definitions we had of them inaccurate, false, and incomplete, and even require us to establish new ones”). Consequently, the spider is classical (purified) in its expression, but baroque (chaotic) in the corpus / body that it targets (dictated by the prior source, or the subsequent function). Concepts such as 'beauty' or 'utility' are meaningless per se. They exist within us, like the thread of the spider which ponders the leap, fall, or void. That which is inherently useful is beautiful. That which is inherently beautiful is useful. Both are measured by their effectiveness, like the almost invisible web that catches flies.

Now imagine Arachne. She has some of the tenacity of Penelope (when we say "Penelope" we might just as well say "spider", or "author", or "actor"). It is no coincidence that the Latin root for the word 'text' is shared in common by the words 'textile', 'texture', or the musical term 'tessitura'. Or that “tela” (port.), “toile” (fr.) or “web” (eng.) all refer to a net, or internet/structure. Ordered, calculated and logarithmic, and yet chaotic, beautiful and uncontrollable. The myth of Arachne (like the story of Penelope) refers, to an inevitable tension, in the text and in the canvas, between creation, which is life, and destruction, which is death. Creation is as natural or necessary as the punishment of the gods is inevitable, inflicted upon every mortal who dares to defy the gods.

You are

Arachne. Therefore, dare to know.

Maria Luísa Malato

[1] The designation refers to printed text only.